What is the difference between a broken heart and a heart cracked open? It’s not a distinction I had much insight into until early April 2025, when I felt my heart shift from sodden leadenness at the state of the world into something much more tender yet capable of joy. This shift allowed me to access a sense of agency and hopefulness that had been feeling very remote. For me, the path toward openness was through hands-on service. And it was especially powerful that I learned this lesson in Israel, on a service-learning trip jointly offered by Yahel: Israel Service Learning and Repair the World, on whose board I sit.

As a rabbi, I have long thought about the concept of service. The Hebrew word avodah is most often translated as “work” or “labor,” but its biblical roots also refer to the complex set of rituals and practices offered by the kohenim and leviim, the priests who served in the Temple in Jerusalem. This ancient understanding has carried through Jewish history and experience to suggest the possibility that work or service could be infused with holiness and purpose. From a young age, I sensed in myself a tendency toward workaholicism, which led me to commit myself to the non-profit sector. I wanted to make certain that, if I was going to work very hard, it would be for something meaningful. Ultimately, I chose the rabbinate as a profession, which I have understood, along with my leadership as the CEO of Reconstructing Judaism, the central organization of the Reconstructionist movement, to be avodah—at the intersection of work and religious service. When I volunteer, I have sought out opportunities where I could most make an impact through my strengths (and within the travel demands of the CEO of a continental networked organization). This has largely meant serving on the boards of (other) amazing non-profits, including Repair the World.

The Hebrew word avodah is most often translated as “work” or “labor,” but its biblical roots also refer to the complex set of rituals and practices offered by the kohenim and leviim, the priests who served in the Temple in Jerusalem. This ancient understanding has carried through Jewish history and experience to suggest the possibility that work or service could be infused with holiness and purpose.

The joint mission between Yahel and Repair was organized around the Service Matters: Israel Summit, which brought Israeli NGO leaders together to explore how to mobilize meaningful, learning-based service in Israel for international volunteers. Before and after the summit, leaders from organizations in the US-based Jewish Service Alliance, a coalition of Jewish organizations that have made a commitment to enhance and expand service opportunities that is powered by Repair the World, participated alongside Repair the World and Yahel staff in our own service learning mission. As a Repair board member, I was invited to come along.

On this trip, we quite literally got our hands dirty day after day. Guided by Dana Talmi, Yahel’s founder and executive director, Yahel’s regional coordinators in Israel’s north, center and south regions ensured that we visited with, learned about and served at NGOs across the country. In Haifa, we helped to spruce up Beit Maya, a family therapy center that aids parents in gaining parenting skills. In Jerusalem, we met with Drori Yehoshua and Mahmoud Schada at the Shalom Hartman Institute to hear about their extraordinary friendship and pack vegetables with them for distribution to families in need in East and West Jerusalem. In Segev Shalom, we met with leaders of Bedouin Women for Themselves and helped them pack food packages to bring to unrecognized Bedouin villages in the Negev. And more and more and more. Doing this work through the auspices of Yahel, which would be bringing the next volunteer group to pick up where our group left off, offered reassurances that our efforts were more than helping volunteers feel good.

Not every visit involved service, but all involved listening and learning—powerful texts and even more powerful stories. In the north, we met Anat Farkas, who founded Bustan Thom in memory of her son, a fighter pilot who died in in the Second Lebanon War, and heard how she seeks to demonstrate the interdependence of all beings through the organic, experiential environmental center powered by Israeli and Arab volunteers. At the Nova festival memorial site, Shalev Biton shared his story of October 7. The story was full of terror and grief, but Shalev’s main take-away was the hope he received in being rescued by Younis Alkarwani, a Bedouin Muslim, offering to us Younis’ actions on that terrible day and their abiding connection following it as a model for going forward. There was an added layer of surreality as we listened to Shalev for more than an hour and could hear explosions coming from nearby Gaza as the Israeli military resumed the war that has gone on for more than 18 months. In Ofakim, a development town hard hit on October 7, we learned from Yahaloma Zechut, a former military airplane technician and survivor of multiple terrorist attacks. She established Ofakim’s first resilience center to empower local residents to act on their own behalf rather than waiting on anyone else.

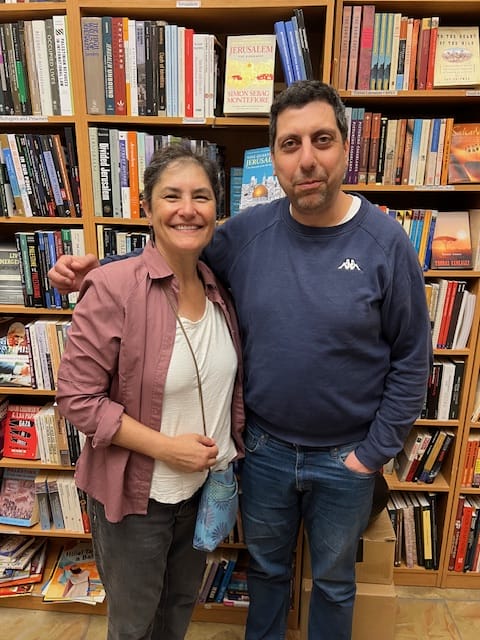

Though our schedule was ambitious and demanding, I carved out time for a few additional visits not on the itinerary. It was non-negotiable for me that I went to one of the Saturday night demonstrations in support of the hostages. Tel Aviv, with the biggest and most diverse demonstrations, was too far to travel for me to after Shabbat. I attended Jerusalem’s more intimate demonstration, which included teenagers sitting in a row with yellow blindfolds holding posters of hostages still in captivity, speeches asking how the Jewish people could celebrate a second festival of freedom with hostages still in captivity, and the reading aloud of the names of all 59 hostages. And I made certain to visit the Educational Bookshop in East Jerusalem, a mostly English-language book store that is a place of discussion and learning dedicated to Middle Eastern culture and the Arab-Israeli conflict that I had visited previously with Encounter and on other occasions.

The bookshop had been raided twice in the previous month and its owner, Mahmoud Muna, arrested and held in jail overnight—for no reason other than, it seems, intimidation. Mahmoud shared an immensely distressing story about the degradation of democratic norms in Israel: searches for “seditious materials” by soldiers who could only read Hebrew (the most seditious thing they found were copies of the Ha’Aretz newspaper, which has been deeply critical of the Netanyahu government), a prison system that immediately dehumanized him, a judge who all but laughed at the aprocedural and flimsy pretext used to arrest him and ordered his release. He also shared how moved he has been by the outpouring of solidarity and support from around the world, saying that he now understands the significance when people act on that word “solidarity.”

At a panel at the service summit, Ohad Yron, who directs sustainability programming for Birthright Israel, observed, “The massacre that happened on October 7 is not ‘a’ or ‘the’ Jewish story. The massive volunteer effort that happened immediately after, both in Israel and internationally, and in the wake of the government’s failures—that is the Jewish story.” This is something that most Israelis, perhaps most Jews around the world, have internalized. Less acknowledged and even less processed is that the Israeli military response in Gaza is also part of the Jewish story, even as the first emerged in the absence of government action and the second is directed by the government. One of the many challenges of the moment is ensuring that the generous, open-hearted nature of the volunteerist response prevails over what both preceded and has followed it.

Our last service stop was at Rucca Farm on Moshav Hemed, which provides therapeutic services to veterans with PTSD. After detailing many complexities, Nir Lahav, its founder and board chair, explained, with typical Israeli irony, that the biggest challenge they face is staying on top of the weeds that grow because of their choice not to use chemicals. As I hoed through and hand pulled 10 yards of weeds—a tiny fraction of the many acres under cultivation—I thought of early Zionist A.D. Gordon’s conviction that connecting with nature and working the land would lead to both personal renewal and the renewal of the Jewish people. I thought about the small-group meetings I have had on previous trips to Israel, where I wore professional clothes instead of jeans and a work shirt—meetings with Benjamin Netanyahu, Naftali Bennett, Isaac Herzog and others. I am not giving up my “day job” or the strategies and tactics that CEOs primarily use, but when Nir told us it was time to stop weeding, I looked over my work and felt a greater sense of confidence that I had really made a difference than during any of my other undertakings in Israel.

As I hoed through and hand pulled 10 yards of weeds—a tiny fraction of the many acres under cultivation—I thought of early Zionist A.D. Gordon’s conviction that connecting with nature and working the land would lead to both personal renewal and the renewal of the Jewish people.

Ecclesiastes Rabbah 1:16 observes that the heart can express more than 60 emotions and offers a biblical prooftext for each of them. Our hearts can see, fall, rejoice, weep, be hardened and so much more. In my experience, service shrinks our complex and overwhelming world into a microcosm that allows us to regain a sense of control and, as Cindy Greenberg, Repair’s CEO observes, to catch a glimpse of how the world should be. In these fractured times, when we need new visions and new pathways, when it is so easy to feel broken-hearted, let us make a commitment cracking our hearts open, accessing our agency, making manifest our interdependence and forging our way toward creating the world we want to see and live in—through any and every means we can devise, including through service.