What do you do when the world you live in suddenly appears to be the opposite of what you thought?

The Jews responded by inventing Purim.

Purim is the holiday of opposites. We celebrate Purim with satire in our dress, behavior, storytelling and music. Purim is a holiday of masks, not the least of which is the façade of a carnival that conceals serious messages. Purim is an adult holiday masquerading as a children’s party. The book of Esther that we read on Purim is a farce pretending to be historical.

Customs of Purim cross many boundaries, poking fun at rituals that anchor most Jewish holidays. Giving tzedakah in a righteous, selfless way is augmented by sharing tasty treats with friends. Who hasn’t vied for the reputation for making the best hamantashen? Even sacred ritual language gives way to parodies of evening prayers or a mock kiddush. One of the main mitzvot of Purim is to celebrate a feast with friends. (See Ezra Weinberg on the Purim seudah and its most raucous aspects.)

While Purim may appear to us like Mardi Gras, it is reminiscent of the carnival holidays of many other cultures as well. Its origins may be traceable to a Persian or Babylonian carnival festival that took place around the vernal equinox. It is likely that Jews adapted carnival customs of Christian Europe during the 15th and 16th centuries for their Purim celebrations, including appointing a Purim king (later, a Purim rabbi), similar to the jester-pope. This custom survives today in the form of Purim Torah, a parody of traditional texts and the Purim shpiel, a satirical play or series of skits.

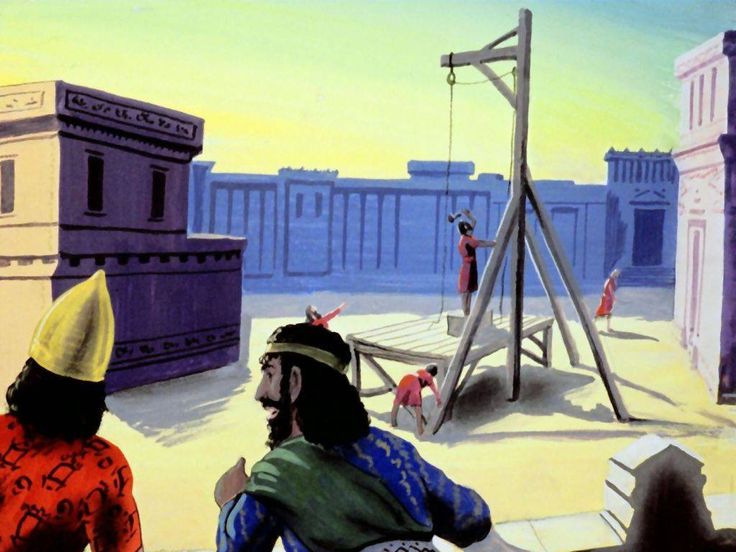

All of these elements of turnarounds and frivolity can be found in the book of Esther itself: King Ahashverosh and his lavish banquets, Queen Vashti’s bold resistance to the king’s harassment and abuse, drunken (mis)behavior, sexual puns and the comic juxtaposition of Blessed Mordechai and Cursed Haman. The tables are turned several times in the story, often in humorous ways. Spoiler alert: At the end of the story, the villain is replaced by the victim. Haman is hanged on the gallows intended for Mordechai, and Mordechai is elevated to Haman’s previous office. The Jewish people are saved and ordered to celebrate the day that “had been transformed from one of grief and mourning to one of festive joy.” (Esther 9:22)

Good conquers evil. At least for one day.

In fact, the book of Esther acknowledges this theme of reversals explicitly at the opening of Chapter 9:

“And so, on the thirteenth day of the twelfth month — that is, the month of Adar — when the king’s command and decree were to be executed, the very day on which the enemies of the Jews had expected to get them in their power, the opposite happened (v’nahafokh hu), and the Jews got their enemies in their power.”

With this opening to the chapter that also includes mass killings of Haman’s family and followers, the author signals that the narrative that follows is not to be taken literally. The chapter draws the topsy-turvy theme to its full and dark completion, substituting the destruction of the Jewish people’s enemies for their own intended doom.

Are these reversals Divine miracles? Reconstructionists look beyond supernatural explanations to explain historical events. Yet even the Megillah itself avoids ascribing Divine power to anything that happens in the book of Esther. In fact, you will not find a single name of God in its 10 chapters.

I see in this absence a message that Reconstructionists can embrace: Power comes from within human beings when we use it in the spirit of godliness. In a key moment of transformation, Mordechai tells Queen Esther that perhaps she has attained her (demeaning yet powerful) position for just such a moment. While Esther is powerful, she must take a great risk to enter the king’s court uninvited. She strategically arranges to speak truth to the real power in the court, boldly and publicly. At the climax of the tale, Esther’s shocking revelation that she is a Jew dramatically upends Haman’s and the king’s own plans. Esther grasps the power, proudly and successfully embracing her purpose.

Reconstructionists look beyond supernatural explanations to explain historical events. Yet even the Megillah itself avoids ascribing Divine power to anything that happens in the book of Esther.

The Purim story tells us that, just as Esther’s courage leads to flipping the script, when we recognize our own power and focus on our individual purpose we can change history. Or as R. Nachman of Bratslav famously taught (in a quote that is equally famously misquoted): “Know that when you have to cross over a very narrow bridge, what is essential is not to be overwhelmed by your fears.” When we refuse to fall prey to our fears, we open our eyes to discover our own power. Like Esther, we can meet this moment if we turn our fear upside-down.

When our world seems topsy-turvy, the Purim celebration gives us permission to laugh at our oppressors. Though we have legitimate fears of the whimsy of tyrants and kings, now and in our past, Purim allows us to mock the tyrants and even fantasize their destruction.

I embrace the masks of Purim as an additional form of resistance from the Jewish toolkit, as well as a way of preventing us from the overwhelming temptation to despair. Let’s embrace humor for one day to overcome the darkness and find solace in frivolity. May we have the power to turn the world right-side up again.