A budget is an implementation document, a part of an overall plan. It is a plan expressed in monetary terms that help define financial questions and answers within the diverse mix of a community.

We create budgets for the same reason we create other plans – so that the use of our limited resources will be consonant with our values and priorities. In the final analysis there may never be enough resources for everything we want to do- but there can be increased financial capacity to realize our mission.

All of our resources are finite. We have a limited number of staff. We have a limited quantity of volunteer hours. Our buildings have a limited amount of space, and so on. Our decisions on allocating these limited resources should incorporate our core values and priorities, so that while the resources may go through cycles, what we stand for is evident in what we spend on.

All budgets have a revenue side and an expense side. While the two sides are always closely related, in most budgeting processes one side clearly sets the tone. In a values-based budgeting process, it is often the expense side that leads.

Detailed budgets are useful for the budget committee. Other constituencies, such as the Board and the membership, may benefit from summary budgets.

Budgeting begins with a clear institutional vision, with the questions:

- Who are we?

- What are our needs?

- What must be done?

The answers to those questions (which are solicited from membership, from committees, from staff) are communicated to the budget committee. The budget committee is not responsible for determining the synagogue’s priorities and direction. It receives that information from the Board or Executive committee and, with its unique expertise, provides projections, offers options and explains the consequences of the various choices to the decision-makers. In small communities many of the same people may sit on both committees. In such a case, they must understand that they wear different hats when envisioning priorities and when allocating.

How and when discussions take place and under what conditions has as much to do with the reception of a budget and its outcomes as the content itself. In Reconstructionist communities we value how we get to our goal (process) as much, if not more, than the destination we arrive at (outcome).

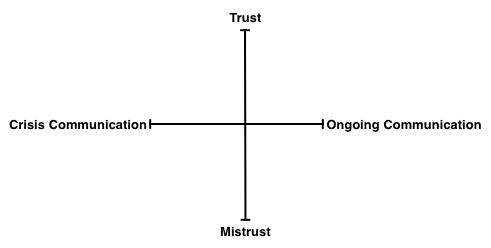

You can take the pulse of your own community’s way of dealing with money and finances by asking yourselves the following:

- Do we discuss money issues in an ongoing way in our synagogue or havurah, or only when we are in financial crises?

- Do some groups in our congregational system deal with money openly and others only when there is a real problem?

- Do we feel complete trust in our leadership and their allocation of funds or do we question how money is being taken in and spent?

Using the graph below, where would you place yourself in answer to the questions above? Would you place your community in the same location?

The communication and trust climate around financial issues in your community will often effect the budgetary process in its formation, implementation or reception by the leadership, staff and membership. Are the core questions of “what can we afford to do?” and “what can we not afford to do?” discernible to everyone?

BUDGET TIPS

- Present the budget in many formats: Functional expenses, program expenses, committee expenses, etc depending on your audience. Break down costs so people can connect the small expenses to the larger sums and understand what events cost, how finances are managed and how programs that are part of the mission of the community touch their lives and are valued.

- Determine whether you see offerings such as education as a fee for service or to be subsidized as part of communal responsibility.

- Make sure you factor in expenses such as compensation time, sabbaticals, parental leave, vacation, environmental impacts (heating, air conditioning, roofing, conservation and environmentally friendly upgrading costs, etc. in a conserving way), ritual decisions around food, fair-wage for care-taking staff, and so on.

- Try to avoid wasting money on cheap short-term decisions (e.g. computer systems), and ensure proper investment in infrastructure by doing it right the first time!

- Add cash flow projections to the budget showing what will be coming in and what is expected to go out over twelve months (building or rental, salaries, programs).

- A great looking budget may have months of crises built in to it because of miscalculated cash flow. Monthly membership dues payments for annual dues can ensure a more even cash flow.

- Build relationships locally with your local Jewish Federation and other Jewish or non-profit agencies where funding, financial services and consulting may also be available.

- Contact the RRC or other Reconstructionist congregations for examples of budgetary approaches.

This resource was originally developed by Rabbis Shawn Zevit and Jonathan Malamy.