For so many of us, and in many different ways, this will be a difficult year to celebrate Passover.

The joy of Passover comes from celebrating the signature moment of liberation in our people’s history, but how can we celebrate in these troubling times with ongoing violence in Israel and Palestine, and a U.S. government undermining civil liberties and human rights? As we know, Jews have experienced persecution and oppression in many times and places through their history and never refrained from having a seder. Indeed, many elements of the rabbinic seder incorporate awareness of the threats to Jews. But for most Jews in North America, what we are experiencing now is quite different and perhaps completely new in our lifetime. How should we celebrate the ancient moment of redemption while acknowledging the pain and suffering of the current moment?

There is no one right way to answer this question — we all make our seders differently. I think we could begin by reminding ourselves what makes a seder such a meaningful spiritual event. To do that, I want to look to two important modern Jewish teachers who remind us that the seder’s spiritual power comes from the way it embodies communal memory. First, I want to look to the German-Jewish philosopher Martin Buber, who spoke of the power of memory in a 1934 lecture about the study of Jewish texts.

Addressing a community of adult Jewish learners at the Lehrhaus in Frankfurt, Germany, Buber stated: “We Jews are a community based on memory. A common memory has kept us together and enabled us to survive … (this) means that one generation passed onto the next a memory which gained in scope — for new destiny and new emotional life were constantly accruing to it — and which realized itself in a way we can call organic.”

For Buber, the passing down of communal memory from one generation to the next creates a “factual connection between generations. Sons and grandsons have the memory of their fathers (and) forebearers in their bones.” This emerges because of “the passion to hand down which kindled (in) each of our sons the moment he became a father. He had to ‘remind’ others of what he was reminded of.” Strikingly, Buber acknowledges that the handing down of memory from generation to generation involves both continuity and change. Each generation shapes the communal memory in its distinct way, while retaining core elements of the story and the passion to transmit it.

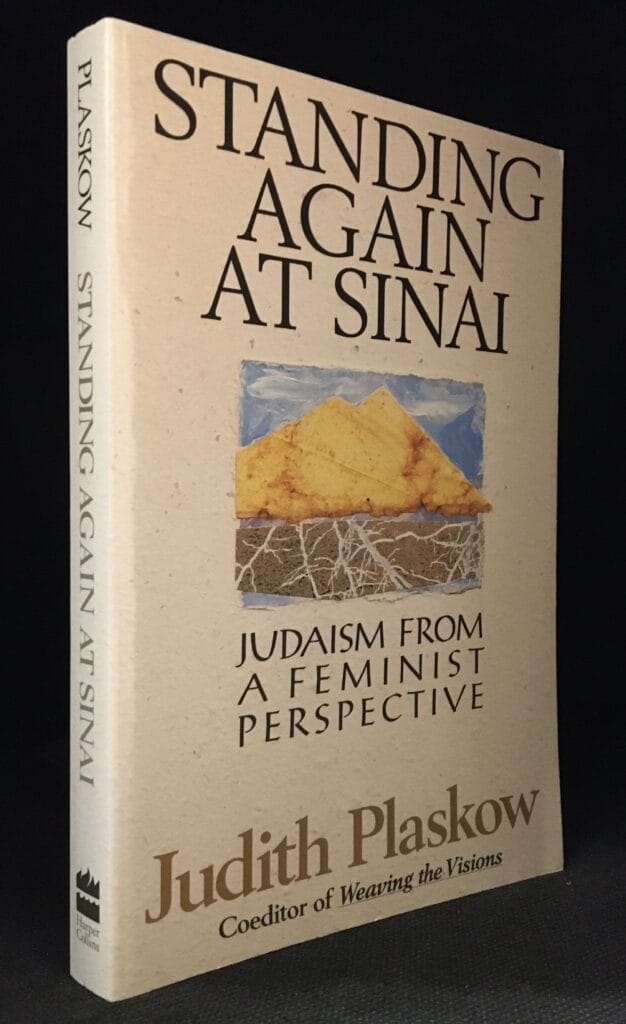

Contemporary Jewish feminist theologian Judith Plaskow builds on Buber’s account to understand the task of feminist reconstructions of Jewish memory. In her pathbreaking book, Standing Again at Sinai, Plaskow writes that because memory shapes our communal and personal identity as Jews, we inevitably integrate our own understanding of those memories into the way we recount them.

She explains: “Many versions of the past feed and sustain Jewish existence, but memories expanded and slightly reshaped with each generation have for centuries been handed down from parent to child, and with them a certain set of attitudes toward the past and toward the world. It is (through) telling our stories of our past as Jews that we know who we truly are in the present.”

For Plaskow, communal memory does not give us a static past that we merely accept. We reshape communal memory to reflect who we are now and forge a synthesis of past and present to understand who we are.

Plaskow, in speaking about the power of the Passover seder, also observes that, “in the modern era, the memory of slavery in Egypt has also taken on (a) more specific meaning. It has fostered among some Jews an identification with the oppressed that has led to involvement in a host of movements for social change – and has fueled the feminist demand for justice within Judaism.”

We Jews are a community based on memory. A common memory has kept us together and enabled us to survive … (this) means that one generation passed onto the next a memory which gained in scope...

Martin Buber

At a politically charged moment such as our own, it may be helpful to remember that connecting the Exodus to social justice and political action is a deeply meaningful way to express our connection to the Jewish past. Yet it is not the only way Jews have done so. I say this because it might be important to give people the choice about whether or not to connect the seder to the political realm. For some, a seder that responds to contemporary forms of injustice is the most meaningful way to express our communal memory. For others, telling the story without making it relevant to today’s events may be more compelling because it places the emphasis on a story we did not ourselves experience or create, but one handed down over generations.

Whatever approach one takes, it is important for all of us to be mindful of Buber and Plaskow’s teaching that what makes memory powerful is that it is forged from an intergenerational bond. Many Jews remember the seders of their childhood and yearn for the warmth and sense of connection it brings. Of course, not everyone who has a seder grew up Jewish, and not everyone does so with parents or children. Many people gather in networks of family, friends and community to share the journey to redemption, and in these settings, we can each be like the parents and children of the rabbinic seder, sometimes asking the questions and sometimes telling the story. What is important, I think, is for everyone at the table to be able to share in the telling, to have their version of the story heard, and to shape the memory of our people’s redemption.

Never in my lifetime have I seen the Jewish people so divided by major political questions, and I don’t think the tensions of the current moment will go away any time soon. Sometimes these political issues divide families, communities and groups of friends. If we can find a way to weave our political passions into our Seder experience while maintaining the “organic” or “factual connection” about which Buber spoke, then that is all for the good.

But we have other ways for the Passover story to bind us together, even as we tell it differently. In the Haftarah recited on Shabbat Hagadol, the Shabbat right before Pesach, the prophet Malachi speaks of the coming of Elijah, whose presence we invite to every Seder. Elijah’s task, Malachi says, is to “reconcile parents with their children and children with their parents.” May all of us have Seders where we, as both parents and children, become reconciled to one another through the power of memory.

Hag Sameakh.

References

Martin Buber, “Why We Should Study Jewish Sources” in Israel and The World, pp. 146-148.

Judith Plaskow, Standing Again at Sinai, pp. 28-31.