By the standards of geology, 100 years is a nanosecond. Yet stretching farther than most human lives, a century tests the limits of human perspective. In 1922, thanks to the ratification of the 19th amendment, American women had just gained universal suffrage (though it would be decades before many women of color could exercise that right in practice). Also that year, the first radio was installed in the Harding White House, the Lincoln Memorial was dedicated, and construction began on New York’s Yankee Stadium. The United States was three years into its experiment with prohibition. Jim Crow was the law of the American South and would be for another 40 years.

And, on January 19, 1922, Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan and his followers founded the Society for the Advancement of Judaism (now known as SAJ: Judaism That Stands for All), the first Reconstructionist congregation. With the newfound freedom of the pulpit, suffrage still fresh on American minds, and Judith — the oldest of his four daughters, having recently turned 12 — it’s no surprise that he was thinking about how to mark the occasion in a religious context.

Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan and family in 1916

On Saturday morning, March 18, Judith (known in adulthood as Judith Kaplan Eisenstein) was invited to cross into the men’s section of her father’s synagogue. Standing in front but not rising onto the bimah, she read from the humash, a written book of the Torah, rather than the traditional Torah scroll. With this act, and over the objections of her grandmothers, Judith became the first individual bat mitzvah in history. Though the ritual was unprecedented, as Kaplan Eisenstein noted many years later, at the time, “No lightning struck. No thunder sounded.”

The bat mitzvah is emblematic of what Reconstructionists believe so deeply— that the Torah should be accessible to everyone: Even more so, our Torah is richer for the diversity of voices and identities within the Jewish community.

Now, in 2022, the twin centennial anniversaries of the founding of the first Reconstructionist synagogue, followed by the first bat mitzvah, are being celebrated by SAJ, the Reconstructionist movement and the wider Jewish world. Taken together, the programs and commemorations are framing a larger conversation about the past, present and future of a Reconstructionist approach to Judaism. The anniversary is bringing back to the fore long-running questions about the meaning of the 1922 bat mitzvah, the relationship of that ritual and the full inclusion of women in Jewish life, and what next steps are needed to keep widening the tent. These conversations are coming at a time when the bar/bat mitzvah is notably evolving, with non-gendered liturgy and even the name of the ceremony itself making more space for non-binary teens. With many congregations across the Jewish world making it possible for kids of all abilities to take part, including many who struggle with rigorous Hebrew demands, the substance of Jewish coming of age ceremonies areundeniably shifting.

SAJ is hosting a series of public programs throughout the year that kicked off in late January with a Centennial Shabbat Service. The series is featuring speakers and conversations about the core ideas established by Kaplan at SAJ’s founding, including a June academic symposium.

Logo for Rise Up | Bat Mitzvah at 100 from the Jewish Women’s Archive and SAJ

Additionally, SAJ is partnering with the Jewish Women’s Archive on a national initiative called Rise Up/Bat Mitzvah at 100. At least 100 synagogues across the Jewish denominational spectrum, including Reconstructionist Congregation Dor Hadash in Pittsburgh, are set to observe the occasion. Commencing with a March 17, multi-access panel discussion, Rise Up also includes the Judith Kaplan 1922 Instagram Project, a social media performance reimagining her experience in a digital, visual medium.

Highlighting the bat mitzvah anniversary will also play a major role at B’Yachad: Reconstructing Judaism Together, the Reconstructionist movement’s March 23-27 Convention, being held online and in Tyson’s Corner, Va. One program, to be led by Rabbi Tamara Cohen of Moving Traditions, will explore the 100th anniversary of the bat mitzvah in the age of gender-neutral celebrations. Still another will honor the legacy of Kaplan Eisenstein, a noted musicologist and influential composer, who earned a Ph.D. at the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion and later taught at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. In her honor, the convention program will focus on the evolution of Jewish music.

“The bat mitzvah is a milestone that is celebrated in every Jewish denomination. Even though the event wasn’t so significant, and the bat mitzvah looked very different in 1922 than it does today, it started a revolution of egalitarianism in Jewish life, where, as time passed and girls took their place, girls and women demanded equal footing with their male counterparts in all areas of religious life,” said Rabbi Lauren Grabelle Herrmann, who has served SAJ since 2015 and is a 2006 graduate of the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College.

100th anniversary celebration of SAJ, photo by Matthew Capowski

In addition to co-organizing the National Shabbat with Jewish Women’s Archive, Herrmann composed new liturgy to celebrate the anniversary of the bat mitzvah.

“The bat mitzvah is emblematic of what Reconstructionists believe so deeply— that the Torah should be accessible to everyone: Even more so, our Torah is richer for the diversity of voices and identities within the Jewish community,” added Herrmann.

Judith Rosenbaum, CEO of the Jewish Women’s Archive, said one reason she thought it important to highlight the bat mitzvah anniversary is that the ceremony has become so ubiquitous that many teenage girls don’t realize that their grandmothers may not have had one or that their mothers may have had a ceremony that looked very different from their male classmates.

“If you don’t understand history, you don’t understand how change happens, which makes it harder to continue to make change,” said Rosenbaum, adding that the bat mitzvah became ubiquitous in the Jewish world because young girls demanded to be treated equally.

“The first bat mitzvah happened in a Reconstructionist context. It took an innovative thinker and maverick like Mordecai Kaplan to make that happen,” continued Rosenbaum. “It really has had an impact far and wide. Girls have fought for their rights in every movement. It is a universal story about girls advocating a role for themselves.”

Rabbi Deborah Waxman, Ph.D., president and CEO of Reconstructing Judaism, concentrated her academic work on the early history of the Reconstructionist movement. Throughout the year, Waxman is delivering a series of talks related to the anniversary.

One of her goals is to disabuse people of certain assumptions that they may hold about the first bat mitzvah. Notably, Kaplan Eisenstein’s ceremony was very different from a boy’s bar mitzvah at the time and would be all but unrecognizable in most synagogues today. The ceremony didn’t immediately become widespread, though, starting in the 1920s, it was common at SAJ. Even at SAJ, women didn’t enjoy ritual equality — meaning girls could have a bat mitzvah, but after that occasion, they couldn’t receive an aliyah or be called to read from the Torah. That didn’t change until a SAJ vote in 1950 enshrined full religious equality—in part because of Reconstructionist ideology and in part due to advocacy from girls in the congregation.

“Judith Kaplan’s bat mitzvah was not a revolutionary event that immediately changed the world. It was deeply expressive of principles animating Reconstructionism—democracy and pragmatism applied to the Jewish civilization, trust in the Jewish people. It was, essentially, a bold experiment in this new approach to Judaism,” said Waxman.

Though Kaplan, a rabbi, had introduced the bat mitzvah concept, it was the community rather than rabbinic authorities that ultimately gave it a stamp of approval through democratic means, explained Waxman. Following democratic practice led to many of the Reconstructionist movement’s most impactful innovations in the realm of ideas, in the form of transformative religious and liturgical texts and in the area of policy, including the adoption of patrilineal descent as a standard for Jewish practice a full 15 years before the Reform movement, to being the first to ordain gay and lesbian rabbis.

“After Kaplan, we insist that every generation is entitled, even obligated, to reconstruct Judaism to ensure its relevance,” said Waxman.

Rosenbaum pointed out that it is telling that this year also marks 50 years of women in the American rabbinate with the 1972 ordination of Rabbi Sally Priesand by the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, the Reform movement’s seminary.

The first bat mitzvah happened in a Reconstructionist context. It took an innovative thinker and maverick like Mordecai Kaplan to make that happen.

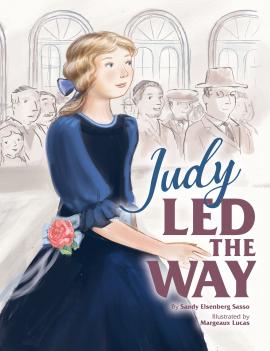

When it opened in 1968, the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College made the pioneering decision to admit women. Rabbi Sandy Eisenberg Sasso entered the following year and in 1974 became the first woman to graduate from the RRC at its third commencement. After a long career as co-rabbi at Congregation Beth El-Zedeck in Indianapolis with her husband, Rabbi Dennis Sasso, RRC ‘74, she is now director of the Religion, Spirituality and the Arts Initiative at Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis. She had known Kaplan Eisenstein as a student and young rabbi and had long been drawn to her story — so drawn, in fact, that Sasso authored a 2020 children’s book called Judy Led the Way. At B’Yachad, Sasso will be speaking about the book and the life of Kaplan Eisenstein; she’ll encore this presentation at other venues, including a virtual presentation to a Hong Kong synagogue. For Sasso, this year represents a chance to honor the life of a pioneering woman who contributed to the Jewish community enormously, well beyond the bat mitzvah, especially to Jewish music.

Judy Led the Way by Sandy Eisenberg Sasso

“We should honor her memory,” said Sasso. “It is very easy to forget the people who made the first steps, the people who made possible other advances and prepared the ground for us to stand on.”

Sasso acknowledged that it was Mordecai Kaplan who was the driving force behind the first bat mitzvah. But it was a 12-year-old girl who had to do what hadn’t been done before—to perform under her community’s spotlight and disapproving eyes of her grandmothers.

“The bat mitzvah is an example of the beginning of creative development of ritual,” said Sasso, who has written numerous children’s books including God’s Paintbrush.

“Now, we have many new rituals to honor different parts of our life cycle and experiences,” said Sasso, who along with her husband, Dennis, created the first covenantal birth ceremony for girls. The two are the first married rabbinic couple in Jewish history.

“We shouldn’t be afraid of change; it is what has renewed Judaism and kept it vital,” said Sasso. “Change requires both humility and audacity, remembering that we are both descendants of a rich past and ancestors to a new generation,” said Sasso.

For Miriam Eisenstein, a longtime member of Adat Shalom in Bethesda, Md., the Reconstructionist movement is the family business. Judith Kaplan Eisenstein was her mother and Mordecai Kaplan her grandfather. Her father was Rabbi Ira Eisenstein, Ph.D., a Kaplan disciple who served as the SAJ’s rabbi from 1931 to 1954. He also was the inaugural president of the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College.

Not to take anything away from her mother’s accomplishment, Eisenstein — a retired civil-rights attorney for the U.S. Justice Department — thinks more focus should be placed on the founding of the SAJ, which gave life to the Reconstructionist movement, rather than the bat mitzvah itself, a single expression of that life.

“I would like people to be thinking about the original tenets of Reconstructionism, including the idea of Judaism as the evolving religious civilization of the Jewish people,” said Eisenstein, also citing the non-supernaturalist concept of God; the Reconstructionist approach to Jewish law as important, but non-binding; and the rejection of the idea of Jews as the chosen people. “What is this thing we are being inclusive about? If that gets lost in the zeal for making it a religion of inclusiveness, then we are missing the point,” she added.

We shouldn’t be afraid of change; it is what has renewed Judaism and kept it vital. Change requires both humility and audacity, remembering that we are both descendants of a rich past and ancestors to a new generation.

At SAJ, some of its younger members have been thinking both about evolving ideas of what it means to be a Reconstructionist and how the movement can be as inclusive as possible.

Koko Onuma, a seventh grader who celebrated her coming of age at SAJ in December, found it meaningful that her ceremony took place so close to the centennial.

“It feels really cool being in the same place where someone else so long ago was pushing society’s limit,” said Onuma.

She noted that the fact that SAJ has begun referring to all ceremonies of B* mitzvah (rather than bar or bat) made her feel part of an inclusive and progressive congregation.

Izy Lusk reading from a prayer book at synagogue

Izy Lusk (she/they) is a high school junior who celebrated her bat mitzvah three years ago. As an assistant in the religious school and the President of SAJ’s BBYO chapter busy planning an upcoming birthday party for SAJ, she says she has been thinking about what it means to belong to a congregation where history was made.

“It is really important to me to continue that legacy and to remember that people have not been having bat mitzvahs for that long,” said Lusk. “It means a lot to know that it happened here in a place that is so important to me.”

(Check out Lusk’s piece on the bat mitzvah in Teen Vogue.)

Lusk has not only been thinking about the past but the future as well. Particularly, she has been focused on the congregation’s plans to gather items to place in a time capsule, to be opened by SAJ congregants in the year 2122. And Lusk is considering leaving something distinctly analog: a favorite book.

What will SAJ look like in 100 years? Inevitably, it will evolve and, in many ways, look and feel vastly different from today. Yet, Lusk is convinced it will remain both vibrant and recognizable from today’s vantage point.

“I am extremely optimistic for SAJ in the future,” affirmed Lusk. “I see them thriving just as much as they are today, if not more. Hopefully, it will be even more expanded, with more families than it has now, while still feeling like a community. I think that no matter the size, it will always feel like a small cozy place.”

Additional Resource:

News Coverage

- Dor Hadash hosts community-wide celebration of bat mitzvah centennial, Pittsburgh Jewish Chronicle

- A new Instagram account tells the story of New Yorker Judith Kaplan, America’s first-ever bat mitzvah, New York Jewish Week

- Manhattan synagogue marks its 100th year as Reconstructionist Judaism’s flagship, JTA