The national holiday celebrating the life of Martin Luther King Jr. offers ample opportunities for service, action and learning. There’s so much to learn about King’s too-short time on Earth. Too often, school lessons or public discussion of King sticks to a few words from a single speech, leaving out much of King’s complexity, intellectual rigor and, yes, political radicalism.

A few years ago, in the hopes of learning more about King’s life and thought, I decided to get as close to the source as I could and listened to Martin Luther King: The Essential Box Set: The Landmark Speeches and Sermons of Martin Luther King, Jr. Hearing King in his own words, for me, brought him to life in a new, vital way. In language that alternated between poetic and prosaic, prophetic and political, he warned us about so much that would transpire if we didn’t heal our national wounds.

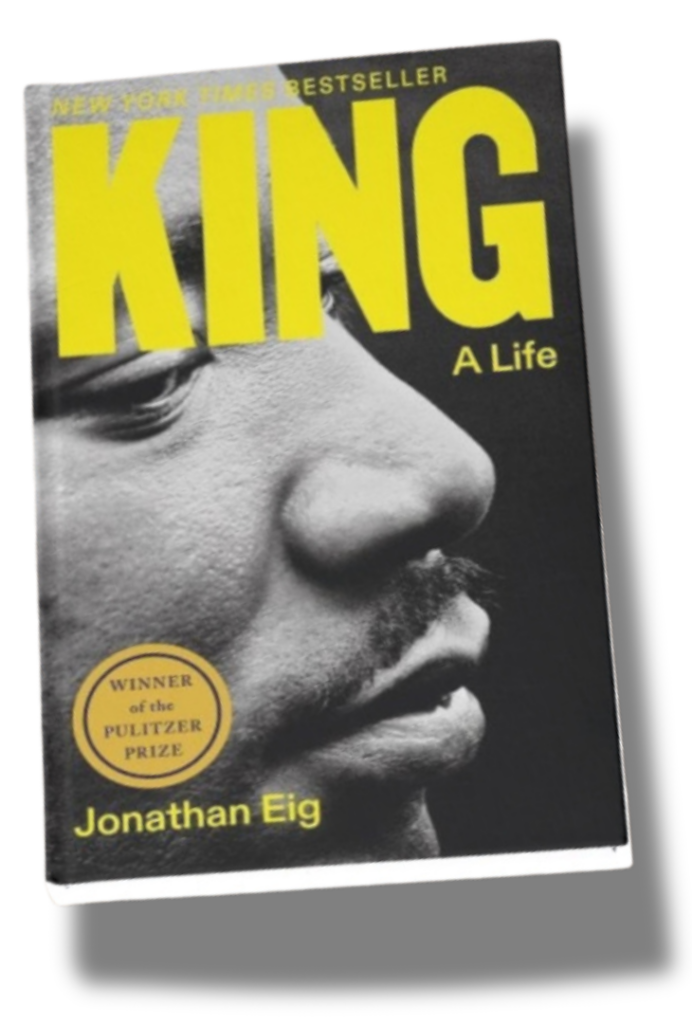

This year, I read King: A Life, Jonathan Eig’s masterful 2023 Pulitzer Prize-winning biography, which was just as eye-opening. A highlight, for me, was the depiction of King’s relationships. I was fascinated by the descriptions of his interactions with one if his closest friends and advisers, Stanley Levison, a wealthy New York businessman. While the book doesn’t spend much time ruminating on the “Black-Jewish relationship” — a subject of countless prior books that too often failed to account for the perspectives of Black Jews — Eig vividly paints a relationship between passionate, complicated men.

Before I get to Levison, I have to sing this book’s praises a little more. Eig’s reporting draws from a trove of previously unavailable materials, including Martin Luther King Sr.’s unpublished biography; audio recordings of King’s wife, Coretta Scott King, made in the months after his assassination in April 1968; and interviews with countless people who knew King before he was famous, including his barber. King is rendered as a fully complex human with faults, fears and anxieties who draws upon his religious convictions and singular talent to galvanize a movement. Anyone interested in how religious leadership can inspire social change in the United States would do well to pick up a copy or download the digital version or audiobook.

In Eig’s telling, Levison was the only Jewish member of King’s inner circle. Like any leader, King leaned heavily on a small, trusted group, and King: A Life recounts many important friendships and alliances. I closed the book thinking Coretta Scott King doesn’t get enough credit and deserves similar biographical treatment. I also left these pages wanting to know more about all members of King’s brain trust, those like Levison and the Rev. Ralph Abernathy — King’s closest friend — who helped King articulate a prophetic vision of a more just world.

Now, I’ve been reading and writing about Jewish life since at least 2001, when I enrolled in graduate school at the Jewish Theological Seminary. I’ve seen many words spilled on the extent to which Jews were involved in the civil rights struggle and ruminations on why that coalition splintered in the mid to late 1960s. For good reason, I’ve seen and read much about King’s friendship with Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, who famously marched from Selma to Montgomery, Ala. But I don’t recall ever hearing Levison’s name. I certainly haven’t seen it celebrated in a Jewish communal setting in connection with the national holiday celebrating King’s birth.

It’s a missed opportunity. Not to hold up Levison as “proof” of Jewish righteousness during the civil rights era or to tokenize an individual. Not to take any focus from important work congregations are doing today to address racism. Certainty not to shift the focus away from King or the movement he led. Rather, it’s an opportunity to learn from history, celebrate the power of relationships, and recommit to combating both racism and antisemitism.

(Note, the King-Levison relationship was also the subject Dangerous Friendship: Stanley Levison, Martin Luther King Jr., and the Kennedy Brothers by scholar Ben Kamin.)

King first met Levison, born in 1912, on a late 1950s’ visit to New York. Levison, an attorney, had made a fortune in real estate and other business ventures. He privately railed against society’s injustices and hoped to use his resources and influence to do good. In fact, as early as the 1940s, he’d been involved with the Communist Party USA, and later contributed to the defense of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, two American Jews executed for spying for the Soviet Union.

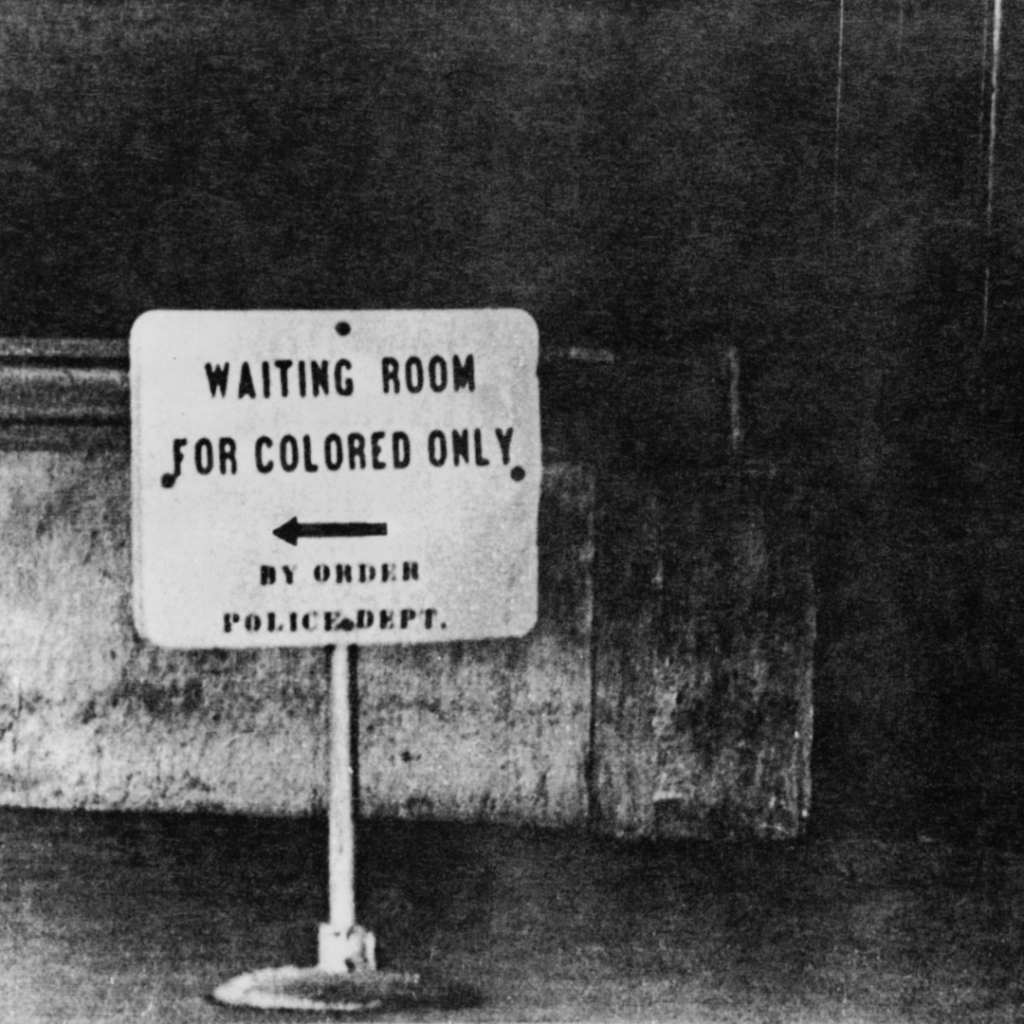

Levison was part of the discussions leading to the founding of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the organization King helped found to marshal Christians and all Americans in a national fight against segregation and racism. Levison served as King’s literary agent and editor (the book includes some feedback Levison gave on King’s writing), advising him on public opinion and dealing with politicians, as well as did his taxes. (We often ask, “What would King say?” but too rarely consult the books he wrote in his lifetime.)

Like many of his generation, Levison was proudly Jewish, serving leadership roles in the American Jewish Congress. Yet he was staunchly atheist, as were others close to King, including Bayard Rustin, the primary organizer of the 1963 March for Jobs and Freedom in Washington, D.C.

One reason Eig had so much information about their relationship is because of his access to transcripts of their phone calls. (It’s also why Eig was able to write in detail about King’s extramarital affairs.) It’s important to remember that the FBI tapped King’s phone virtually wherever he went. In fact, one of the pretexts for doing so was Levison’s former Communist ties. Though, as Eig makes plain, the government never found any evidence that Levison was trying to turn King toward communism; still, the wiretapping continued. The book makes clear the extent of the American government’s malevolent surveillance of King and his allies. Eig makes a compelling case that much of the FBI apparatus, even President Lyndon B. Johnson himself, were complicit in a vast effort drive King from public life and perhaps even drive him to take his own life. Also, for nearly a decade, the FBI devoted previous few resources to protecting King’s life against many legitimate threats. In his time in public life, King was nearly fatally stabbed, his home was bombed, and he was repeatedly physically assaulted. This is a history with which our government and society have not fully reckoned.

In 1967, the FBI captured an unsarcastically terse exchange the two men. In the mid-1960s, after scoring earth-shattering victories that would spell the end of Jim Crowe in the South, King and his allies turned their attention to racism in northern cities, poverty, unemployment, and, most controversially, the war in Vietnam. As the 60s grew more turbulent, King’s popularity among White Americans fell, and many Black activists began to lose patience with his nonviolent, integrationist approach. King’s critics said he should stick to civil rights. Some even described his opposition to the war as un-American.

For King, separating his opposition to racism and war wasn’t an option — both stemmed from his deeply held religious convictions. Political activism was, for him, a religious expression. King sought to clearly articulate these connections to faith leaders, politicians and the public. On April 4, 1967 — exactly one year before his murder — King delivered “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence” at Manhattan’s Riverside Church.

He addressed his critics in a speech that was somewhat cerebral in tone, lacking the soaring rhetoric of best-known speeches in Alabama; Memphis; or Washington, D.C.:

“And when I hear them, though I often understand the source of their concern, I am nevertheless greatly saddened, for such questions mean that the inquirers have not really known me, my commitment or my calling. Indeed, their questions suggest that they do not know the world in which they live.”

Today, “Beyond Vietnam” is considered by scholars to be among King’s most consequential speeches. At the time, it didn’t move public opinion much, according to Eig’s telling. In fact, one of his closest friends said he didn’t get it.

“I am troubled by this speech of yours,” Levison told King in a 1967 phone call, as recorded by the FBI and reported by Eig. “The speech was not balanced. This speech did not typify your expression on this subject.”

“Well, it was probably politically unwise,” replied King, “but I will not agree that I was morally unwise.”

It’s an eternal question in politics: the calculus of determining what is politically right, what is morally right and if there is any point where the two meet.

Despite his progressive ideology, Levison was a political pragmatist. He knew that the speech would irreparably harm King’s relationship with Johnson and, perhaps, irrevocably damage King’s standing in the “White America” of the day. As evidenced by the conversation, King didn’t disagree.

Levison’s atheism may have been part of the reason he struggled to grasp the depth of King’s commitment to nonviolence in all forms. And perhaps that’s why Heschel seemed more in tune with King on the issue of Vietnam. Though, as a secular Jew, Levison was much more representative of Jewish participation in the civil rights movement than Heschel. Marc Dollinger, Ph.D., wrote in Black Power, Jewish Politics of an inverse relationship between religious commitments and Jewish participation in the civil rights struggle.

King, for his part, grew frustrated that people couldn’t grasp or were turning away from his brand of prophetic activism. During this time, Eig recounts King dejectedly telling Coretta that he felt like he didn’t have answers anymore.

Nearly 60 years after that speech and phone call, we live in a vastly different world. Yet racism, poverty and war remain scourges. King’s friendship with Levison and others of different religious and ethnic backgrounds illustrates how no one can change the world on one’s own —how even great leaders must rely on others with different perspectives. Eig’s book also demonstrates how much work was left undone, and how much King and his supporters failed to accomplish. Nevertheless, their example inspires us to this day.

King and his allies had no illusions about the dangers they faced or the enormity of the problems they hoped to help remedy. He famously said that the “arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” He was fond of quoting the biblical prophets and likely wasn’t overly familiar with the Jewish Mishnah. Still, I can’t help but think of one of the most quoted but salient passages of Pirkei Avot: “It is not your responsibility to finish the work, but neither are you free to desist from it.”

What could be more fundamentally Jewish … or American?