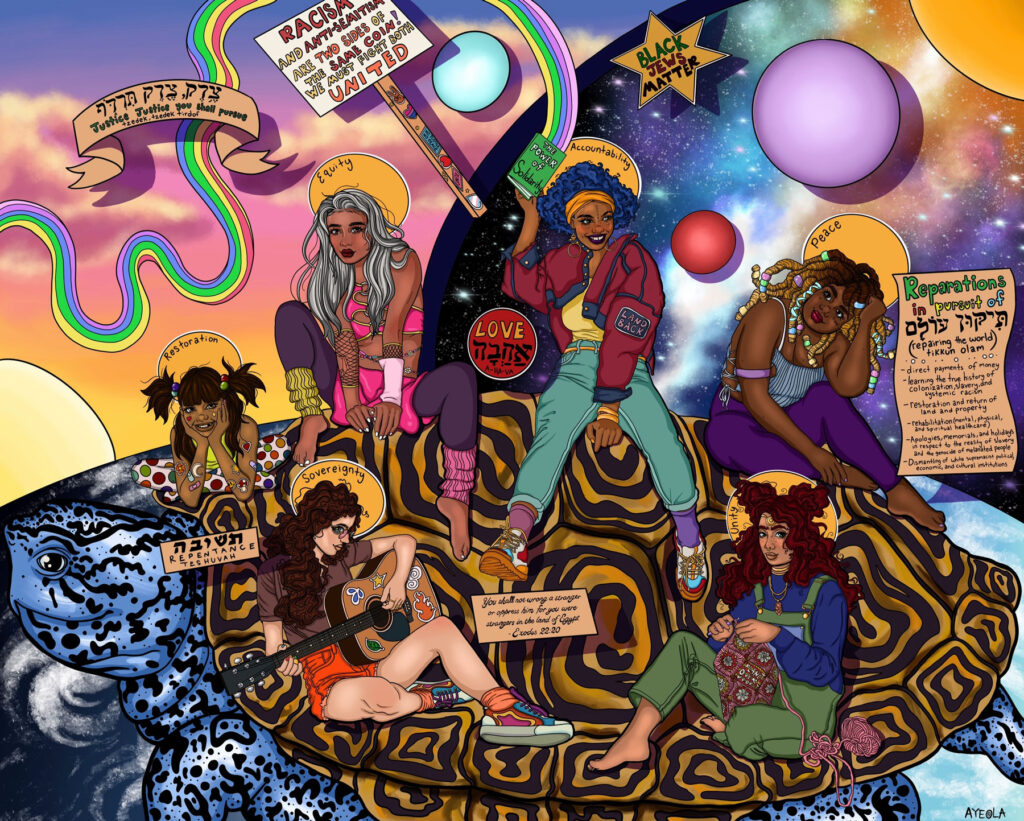

Sandy Gerber, a member of Reconstructing Judaism’s Tikkun Olam Commission, delivered this talk on Jan. 31, 2025 at Mayim Rabim in Minneapolis. The d’var Torah was connected to Reparations Shabbat and Reconstructing Judaism.

Introduction to This Time and Place

Hello everyone! Gut Shabbes and Shabbat Shalom! I’m Sandy Gerber, a member of Mayim Rabim and a member of the Tikkun Olam Commission, which is the racial justice body of our national denomination, Reconstructing Judaism.

How thrilling it is to here, after many months of planning this Reparations Shabbat weekend, which is taking place in Reconstructionist congregations around the country. And how mind-wrenching it can feel, to be focusing on positive efforts to address our nation’s ills in the midst of the despairing national picture we find ourselves in. We’ve experienced less than two weeks of the new regime in power, yet have seen an appalling agenda of crackdowns, takeaways, threats and pullbacks of all kinds of humane and progressive policies.

Reparations Shabbat weekend comes at a fitting time, however, shortly after the Martin Luther King holiday and at the beginning of Black History Month. The Black prophetic and resistance tradition offers us a great deal about holding on and persevering in the face of tremendous odds. So does the Jewish resistance tradition, which emerged even in the depths of the Holocaust.

Reparations Shabbat weekend also coincides with the Torah portion, parashah Bo, which in part has to do with reparations that the Egyptians gave the Hebrews as compensation for enslaving them. As most of us here know — because we at Mayim Rabim helped with its passage — the Reconstructionist movement passed a substantive reparations resolution in 2023. Reparations Shabbat weekend is a means of elevating the struggle for reparations, even in the throes of the grim political climate we’re in.

Why continue to work on reparations when the environment seems so hostile to all things progressive? For one thing, the hardest hits coming down at the moment have the heaviest impact on people of color, whether it’s roundups and deportations of immigrants, abolition of DEI programs and bashing people of color as DEI hires, layoffs of civil service workers in federal jobs, banishing of Black history curriculums, shutdowns of abortion services or the ramping up of dirty fossil fuels. The hits aren’t equally distributed, and neither are the costs. We’re not starting on an equal playing field since so much that’s already owed is past due; therefore, the need to struggle for past-due reparations that are owed to people of color remains constant. This is particularly true in the present moment, when the disparate impact of reactionary policies on white communities and on communities of color will be widening exponentially.

Overview of the ‘1299 Reckoning’ Trip

When Rabbi Sharon Stiefel asked me to give a talk about the move of the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College from the inner city to the suburbs, I asked her what she’d like me to focus on. “How about a few learnings you picked up on your recent trip, a reflection or two?”… . That hit me like a ton of bricks! A few learnings and reflections … hmm; the trip unleashed a firehose of information, learning, food for thought — a huge amount of material to dive into and draw from! Her request was based on a journey to Philadelphia that I participated in last year, to join a seminar organized by the national leadership of our denomination, Reconstructing Judaism.

In May 2024 a group of approximately 15 participants embarked on a week-long exploration of a major move by RRC from its inner-city home in North Philadelphia, where it had established itself in 1968, to the leafy suburb of Wyncote in 1982. The college is the only one in the nation that trains Reconstructionist rabbis. The group participating in the seminar was comprised of rabbinical students, staff and faculty of the college, national board members and staff of Reconstructing Judaism, and members of the Tikkun Olam Commission, which is the racial justice body I serve on.

Many moons ago, in a different time and place — the late 1960s and early 1970s — this experience might have been called an urban plunge. It often happened in Chicago. In the late ’60s, the intent of the Urban Plunge was to arouse the consciousness of mostly white, mostly middle-class college students about their own racial and economic privilege by being thrust into the middle of what were then called impoverished ghettos, mostly comprised of Black and Latino residents.

In 2024, the Urban Plunge was reframed by the Tikkun Olam Commission as “A 1299 Reckoning.” The naming was significant for several reasons. The seminar occurred in the aftermath of the 2023 passage of the national Reconstructionist resolution on reparations for slavery, discrimination, genocide and land theft. The seminar was called “A 1299 Reckoning” because the current address of the rabbinical college in Wyncote is 1299 Church Road. But most of all, the seminar was intended to be a wake-up experience. What were we waking up to? In America in the 2020s, it was not to the external realities of a first-time awareness of severe racial and economic disparities in hard-hit urban neighborhoods. This we were somewhat familiar with.

No, this was about turning the spotlight on ourselves, in our own direction, reversing the typical process of looking at the ills out in the world and asking how we might fix them. The seminar asked us to examine the lay of our own inner land, in conjunction with addressing the external matter of reparations that might be owed to Black and Indigenous communities. What were the consciousness of rabbinical students and staff when rabbis were being trained at the North Philadelphia address of the college before it relocated to Wyncote in 1982? What did they see and understand about the conditions of poverty and discrimination around them? How did they reckon with the Black liberation struggles that had been raging right outside their door? How did they factor in the reality that there had been a major revolt by the community they were located in as they planned to move from 2308 North Broad Street to 1299 Church Road?

I found it remarkable that some 40-plus years later, Reconstructing Judaism was willing to look at the move they made in 1982, and dig into the economic and political realities of North Philadelphia at that time.

Sandy Gerber

Was there something worth examining about the move away from the inner city? How did it relate, or not, to questions of racism? If racism was involved, how is that analyzed and measured? Are reparations owed, and what kind? And, of course, my own personal questions arose, particularly regarding the synagogues that were located in core urban areas of Minneapolis that had taken off for the suburbs. How might the Philadelphia lessons apply?

A quick heads-up: I’ll be using abbreviations during the rest of my remarks: For Reconstructing Judaism, our national organization, I’ll say RJ; for the Tikkun Olam Commission, which is the racial justice body of RJ, I’ll say the TOC; and for the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, I’ll say RRC.

I found it remarkable that some 40-plus years later, RJ was willing to look at the move they made in 1982, and dig into the economic and political realities of North Philadelphia at that time, including the economic situation and racial consciousness of the Jewish community as well as the Black community. And that RJ was seeking to come up with relevant research questions today that could address decisions they made back then. I think this is part of the power of the reparations movement; it gives us a green light to look backward to calculate past due debts as well as look forward, to determine how to take action on those debts in the present and future.

Structure and Content of the Seminar

The trip was organized as a one-week class, with all-day sessions, held at the current location of the Rabbinical College in Wyncote. We immersed ourselves in in-depth nightly reading, morning Torah study on dispossession and accountability, group discussions and daily lectures. We studied policies that shaped urban segregation, Black/Jewish dynamics as allies and opponents, major Black-led economic development initiatives in North Philadelphia and the fierce Black Power movement there.

We heard at least two lectures every day from reparations activists, scholars of Jewish urban politics and migration, academics who studied U.S. government policy related to segregation and disinvestment, and grassroots Jewish activist scholars whose history included involvement in Black liberation struggles. We toured the North Broadway neighborhood of the old RRC, led by an African-American guide who was a realtor with lifelong community activist experience.

One newspaper article that hit me between the eyes was from the Feb. 16, 1969 edition of The Philadelphia Inquirer, titled, “Rabbi College Set in Ghetto.” Two powerful book chapters about Black history in Philadelphia included one on a visionary Black-led economic development program intended to transform the severe poverty in the area and one on Philadelphia’s Black Power movement. Both of these movements were led by dynamic activist Black pastors: the Rev. Leon Sullivan and Father Paul Washington.

I was stimulated by a lecture by a Jewish professor, Lila Corwin Berman, Ph.D., from nearby Temple University, titled, “White Flight and the Jews of America’s Cities,” and I was inspired by lectures and readings by April Rosenblum, a Jewish leftist radical with a deep critique and solid experience in Black/Jewish allyship.

A highlight of the week was a live panel discussion with four Reconstructionist rabbis who were students at RRC in North Philadelphia during the 1970s and right before the move in the early 1980s. The discussion focused on their reflections about their time there and their subsequent thinking about the experience. And I must add that this discussion was enriched by a conversation I had just this past Wednesday with a member of our own congregation, Rabbi Jeffrey Schein, who was an RRC student from 1971 to 1977.

As our week of study progressed, I asked myself whether the title of the seminar should have been called “A 2308 North Broad Street Reckoning” rather than “A 1299 Church Road Reckoning.” And more questions came to my mind about what I thought the RRC folks in the early 1980s might have asked themselves, for example:

- Although we’ve determined that a move would be for the greater good of the Reconstructionist movement and its Jewish adherents, what, if anything, do we owe our neighbors who we’ll be leaving behind with such a move?

- If we didn’t move, how might we contribute more to the political and spiritual movement for liberation that’s surrounding us?

- What might we lose, in terms of connection with oppressed communities that, throughout most of our history we’ve had much in common with, if we uproot ourselves and head into a more privileged community?

- How might the Jewish ethical teachings we study at RRC be informed by what, in Latin American countries at that time, was called Liberation Theology? Liberation Theology led to deep engagement between the Catholic Church and the poor communities in which they operated. How might a Jewish theological institution adopt a form of Liberation Theology and practice?

- How do we change the structure of our learning so that we’re not a mostly remote enclave in a sea of humanity around us, but we’re a more porous organism that’s continually exchanging nutrients between our internal environment and the community around us?

The Rabbis Panel

On the final afternoon of an intense week-long immersion, we had the great good fortune of spending a couple of hours with a panel of four revered long-time Reconstructionist rabbis. In addition to this group’s standing as being very progressive and conscience-driven, they had the singular distinction of having been students at RRC when it was in inner-city Philadelphia. Some of them were there in the early 1970s, when the college was a fairly new arrival on Broad Street. Others were there on the cusp of the move to Wyncote in the early 1980s.

So, what did these rabbis have to say about RRC’s move from the city to the suburbs? One said that in the 1960s and ’70s, the Jewish community was moving from the city to the suburbs, and there was little vibrant Jewish community left in North Philadelphia. Also, the initial requirement for entry into RRC was eliminated — that is, in the early years, the students had to agree to complete a joint degree with adjacent Temple University, one in rabbinical studies and a doctorate in a related field at Temple; that requirement was ultimately dropped. The proximity to Temple, just a few blocks away, had been a driving factor in the co-location of RRC because of the convenience for students.

Most of the rabbi group said that there wasn’t a lot of interaction with the surrounding community because most of the students didn’t live there. Every day, they took the subway to RRC from Center City or Germantown or other neighborhoods further away. Once they arrived at their destination, they didn’t go much beyond Broad Street, a major thoroughfare, because of rumors that it wasn’t safe. One said there was an undercurrent of racism because people at RRC discussed the area as being Black and poor, and not safe; she said the confluence of racism and a fear of high crime loomed large.

One rabbi noted that although the fear of crime was present, he and his wife never experienced it personally and, in fact, experienced a lot of humanity. He said he walked on Broad Street many times and that a person creates their own bubble; he was happy, and, perhaps, should have been more attuned to the life experiences of those who resided there. He described it as a Black neighborhood with pockets of Jewish businesses. He also said that you can’t paint a whole community negatively as a ghetto; life and good times flourished there, too, like going to the stadium to watch the Phillies play and visiting restaurants on the way, including the famous fish and seafood restaurant, Fisher’s.

On the other hand, he noted that his wife was shocked to go into a supermarket where the prices were twice as high as in the suburbs, and the food was on the verge of spoiling. This was an example of what he said were some of the worst aspects of what’s considered a ghetto.

A couple of rabbis talked about how they took a few stabs at grappling with the gap between their being in the midst of the neighborhood, yet being apart from it. In one instance, the students held an open house and invited people in the community to come. But it became clear to them that the problems of poverty around them were too big for a group of rabbinical students, who were interested in having a dialogue, to tackle. In another instance, several RRC students met with a progressive Black pastor, asking how they could be more involved in the community. The pastor said if they could make a 10-year commitment to staying there, they could work together. The students wouldn’t make that commitment, and in any case, immersion in their studies left little time for outside involvement. The partnership with the pastor didn’t materialize.

One rabbi said that almost no one at the school talked about racism and, in fact, students were heavily focused on LGBTQ issues. A couple of the rabbis noted how much they loved the building, with its wonderful architecture and spaces, but their love of the building didn’t seem to extend very much into the neighborhood beyond. Inexorably, the students’ focus evolved into trying to make a difference within Judaism in Jewish renewal and in reconstructing Judaism, rather than in the issues of the wider world.

Once they arrived at their destination, they didn’t go much beyond Broad Street, a major thoroughfare, because of rumors that it wasn’t safe.

Sandy Gerber

he group seemed to agree that a turning point was reached when RRC brought in a new executive director. Although they said he was very progressive, he decided that RRC couldn’t grow in the Broad Street location. The school needed full-time faculty, which they lacked, and they needed to improve their financial picture, which was flimsy and marginal. He said he would only accept the position if the school agreed to move. One rabbi said the agreement to move to a suburban location meant that they accepted the idea that they’d be change agents within Judaism, but not necessarily in the larger societal struggle.

One rabbi said that for many who attended RRC on Broad Street, there was a sense of pride in having studied in north Philadelphia, but, in actuality, they were in North Philadelphia but not of it. Another said that had they stayed on Broad Street, they would have had to face issues of racism: “There was a lot of consciousness about race in the larger society in 1968, the year RRC came to Broad Street. We should investigate how race wasn’t much in the consciousness of RRC, even though we were located in the midst of the roiling community around us.”

In summing up, one rabbi expressed regret that, as he put it, the blossoming of two civilizations and two communities — Black and Jewish — wasn’t able to happen conjointly at that time. But he’d be interested now, in participating in reparations-type work for north Broad Street.

Concluding Thoughts: The Reparations Questions

Among the questions Reconstructing Judaism might contend with, related to the 1299 Reckoning project:

- How do we determine whether harm was done to the community we left behind by our move?

- If harm was done, what kind of harm may have been incurred?

- If we determine that harm was done, what form might reparations take to redress it? And the counter-factual: Had we stayed, how might we have contributed to the well-being of the community?

In current reparations practice, these kinds of questions are foundational to the research that goes into what’s called a Harms Report. A Harms Report serves as the basis for calculating reparations that are owed by a government or an institution. The next big challenge for Reconstructing Judaism could be formulating answers to these questions and potentially fashioning recommendations that attempt to address them.

Further Reading

Explore how Rabbi Mira Wasserman confronts slavery in Jewish sources.

Learn about Reconstructing Judaism’s pilgrimage to Georgia and Alabama.

Review Reconstructing Judaism’s racial justice commitments.

Learn about RRC’s Dismantling Racism from the Inside Out project.

Listen to a podcast about the Dismantling Racism project.

Read Rabbi Deborah Waxman’s call for Jews to embrace the pursuit of racial justice.